If you want, you can create your own Covid-19 vaccine at home and it is actually not that hard to do.

In December 2020, johnswentworth posted the following question on LessWrong: How Hard Would It Be To Make A COVID Vaccine For Oneself? . These are some of the answers they got from user eillasti:

I am not even sure that you need bio/bioinformatics know-how beyond the stuff that you can read up in the wikipedia.

The only complicated ingredient is peptides. You can order their synthesis in a special lab for around $150-$300 per peptide, 4-5 weeks delivery time. The other ingredients you can also buy somewhere. The equipment is trivial, you can buy the whole set for $400 and cook it in your kitchen if you wish.

on the question whether one would need any unusual skills other than some typical wetlab skills, eillasti answered:

No. Not even wetlab stuff, more like high school chemistry lab skills.

Open-source vaccines

It turns out there is a group called RaDVaC (Rapid Deployment Vaccine Collaborative) that has published instructions on how to make your own vaccine at home. These instructions are free and come under an open-source license for everyone to share and build upon.

This is what they say about themselves on their website:

We perform research and development of vaccine formulations that meet 4 minimal criteria:

– General designs are based on decades of published literature demonstrating safety and efficacy in animal models and human trials

– Made from easily obtained and relatively inexpensive materials

– Extremely easy to produce

– Simple and painless to self-administer by nasal sprayer

Part of our R&D is to test the vaccines on ourselves. Before and after testing, we collect saliva, blood, and other samples for analysis to check for evidence of immune responses to the vaccine.

Peptide vaccines and nasal sprays

The RaDVaC design (summarised in a white paper) is a nasal-sprayer vaccine that is based on peptides. Peptides are very very small proteins made of around 2-50 amino acids. These peptides mimic several sub-components of the viral protein, e.g. parts of the spike-protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to bind to human receptors. Other vaccines mostly rely on larger chunks of the protein in some form. These either get injected directly, as with the Novavax vaccine. Or the protein is produced by the body itself, as with the vector vaccines (e.g. AstraZeneca) and the mRNA-vaccines (e.g. Pfizer/BioNTech). The idea with using peptides is that the larger protein chunk gets chopped into smaller pieces anyway. These pieces, called epitopes, is what immune cells react to.

The story is of course much more complicated. For example, small peptides tend to elicit a weaker immune response than larger proteins (this is called immunogenicity). They can easily be degraded by the organism and sometimes are long gone before they elicit an effective immune response. On the one hand that makes them safer to use, as risks of side effects and allergic reactions are minimized. On the other hand this may make a vaccine less effective. Then again you can simply administer the nasal spray more often and you can add a large variety of similar peptides. If you want to lean more, see e.g. this paper for a review on peptide vaccine. I think it’s fair to say that peptide vaccines are promising, despite some challenges.

Having a nasal spray vaccine instead of one that gets injected in the muscle has some notable advantages:

- you get local immunity in your respiratory tract, exactly where you need it. The immunity conferred by injected vaccines is only systemic, which means it is probably slower to react and may not prevent transmissions as effectively

- nasal spray vaccines are very easy to administer and distribute. You don’t need a medical professional to take the vaccine

In that sense the RaDVaC vaccine has a small chance of working even better than the ones that are commercially available. At least the local immunity is likely to provide a valuable complementary contribution.

Creating your own vaccine

Now lets get back to johnswentworth and their journey to create their own vaccine. In another article on LessWrong, called Making Vaccine they explain exactly what they did.

All of the materials and equipment to make the vaccine cost us about $1000. We did not need any special licenses or anything like that. I do have a little wetlab experience from my undergrad days, but the skills required were pretty minimal.

The large majority of the cost (about $850) was the peptides.

The peptides were custom synthesized. There are companies which synthesize any (short) peptide sequence you want – you can find dozens of them online. The cheapest options suffice for the vaccine – the peptides don’t need to be “purified” (this just means removing partial sequences), they don’t need any special modifications, and very small amounts suffice. The minimum order size from the company we used would have been sufficient for around 250 doses. We bought twice that much (9 mg of each peptide), because it only cost ~$50 extra to get 2x the peptides and extras are nice in case of mistakes.

Besides the peptides, all the other materials and equipment were on amazon, food grade, in quantities far larger than we are ever likely to use. Peptide synthesis and delivery was the slowest; everything else showed up within ~3 days of ordering (it’s amazon, after all).

The actual preparation process involves three main high-level steps:

– Prepare solutions of each component – basically dissolve everything separately, then stick it in the freezer until it’s needed.

– Circularize two of the peptides. Concretely, this means adding a few grains of activated charcoal to the tube and gently shaking it for three hours. Then, back in the freezer.

– When it’s time for a batch, take everything out of the freezer and mix it together.

Prepping a batch mostly just involves pipetting things into a beaker on a stir plate, sometimes drop-by-drop.

Why would you want to do this?

The part I found by far most interesting is the one where johnswentworth explains their motivation:

I imagine, a year or two from now, looking back and grading my COVID response. When I imagine an A+ response, it’s something like “make my own fast tests, and my own vaccine, test that they actually work, and do all that in spring 2020”. We’ve all been complaining about how “we” (i.e. society) should do these things, yet to a large extent they’re things which we can do for ourselves unilaterally. Doing it for ourselves doesn’t capture all the benefits – lots of fun stuff is still closed/cancelled – but it’s enough to go out, socialize, and generally enjoy life without worrying about COVID.

I’ve written a blog post about Benjamin Jesty, the dairy farmer who successfully immunized his wife and kids against smallpox the same year that King Louis XV of France died of the disease. I explicitly use this as an example of what Rationalism should strive to consistently achieve. Yet when a near-perfect real world equivalent came along, on super-easy mode with most of the work already done by somebody else, it still took me until December to notice. The radvac vaccine showed up in my newsfeed back in July, and I apparently failed to double-click. That level of performance is embarrassing, and I doubt that I will grade my COVID response any higher than a D.

So I’m doing this, in part, to condition the mental motions. To build the habit of Doing This Sort Of Thing, so next time I hopefully do better than a D.

To me that mindset makes a lot of sense, even if creating your own vaccine may not be worth it anymore given that commercial ones will become widely available within the next few months.

Safety and efficacy

Some people voiced concerns about safety, to which johnswentworth reponsded:

– Peptide synthesis services generally provide various quality control checks on the product (some free, some upcharge). So at least you’ll know what you’re getting.

– Antibody-dependent enhancement [meaning that being exposed to the vaccine can make you more vulnerable to the disease itself] is one of the main things the paper) discusses. It’s pretty rare to begin with, and the cases where it’s happened have some patterns to them which can be avoided; the peptides are chosen to avoid those pitfalls. Reading between the lines, it sounds to me like historical cases were largely a by-product of historical vaccine techniques (e.g. attaching pieces of one virus to the backbone of another in the case of Dengvaxia) which aren’t used here.

– As I understand it, interfering with administration of a later vaccine while also being ineffective would involve basically the same pieces as antibody-dependent enhancement. The paper did not specifically discuss this, though.

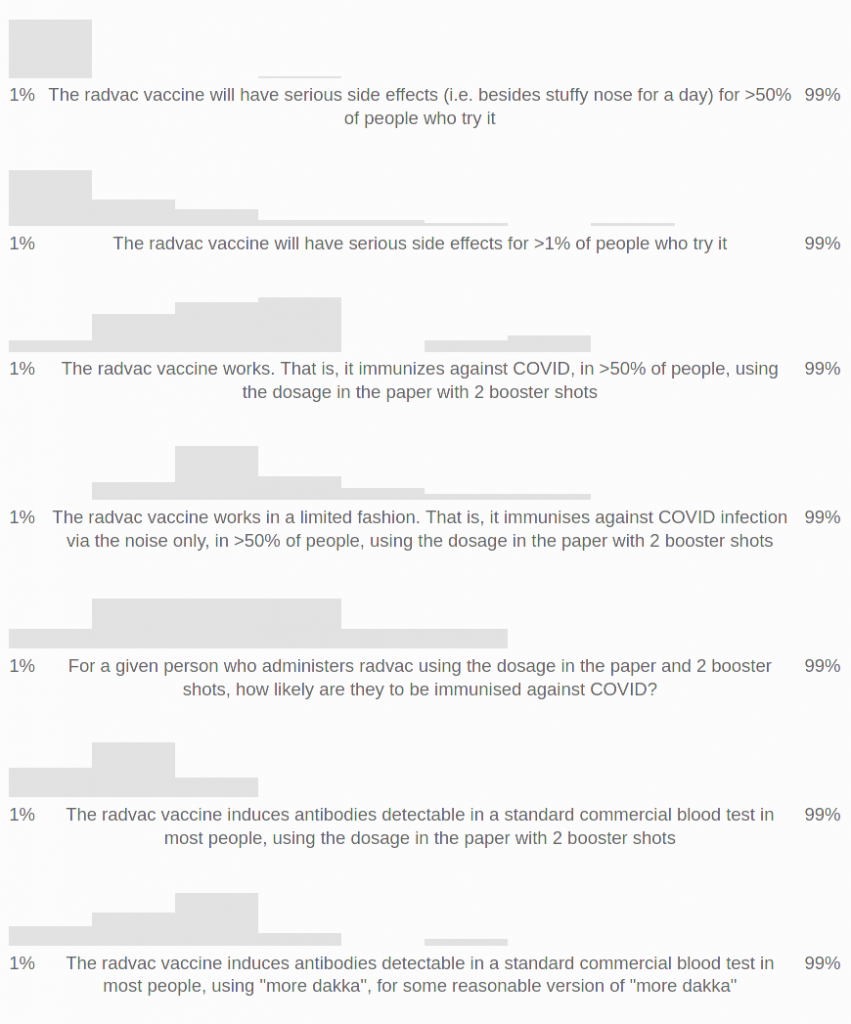

Obviously the vaccine has not undergone formal testing. While a lot of scientists seem to think it should be safe, no one can guarantee it actually is safe. LessWrong being LessWrong, someone opened a prediction poll in a comment under the post. Commenters generally seemed to think the vaccine is probably safe, but are also skeptical about whether it will be effective:

On February 26th 2021, johnswentworth posted the result of a first commercial antibody test result he made to check whether the vaccine worked. Results came back negative, but that was mostly to be expected. Immunity from a nasal spray is likely to be stronger in the mucosa of the respiratory tract than in the blood. One of their future plans is to test for mucosal antibodies specifcly, but that is yet to happen.

Are there any studies on how long a local vaccine is effective? How is the long-term protection if it doesn’t cause a systemic reaction?

So the white paper and the article on LessWrong give some explanations. But I think you would hope for a systemic reaction in addition to a local one. I’m also somewhat unclear on how to interpret a lack of systemic reaction (or at least a lack of antibodies in the blood). Maybe the phrase “Results came back negative, but that was mostly to be expected.” is somewhat misleading, as that expectation includes the fact that they had only gone through half of their planned doses with only a subset of the planned peptides when they did the test. So yeah, I think there is some skepticism warranted whether it works at al and long-term protection is probably even more complicated than that