For the past few months of my PhD in epidemiology I have worked on forecasting and forecast evaluation. In many places, forecast models have had a huge influence on policy during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Imperial model (code here) for example played an important role in the UK government’s decision to go into a lock-down in March. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also rely heavily on predictions made by research teams around the world.

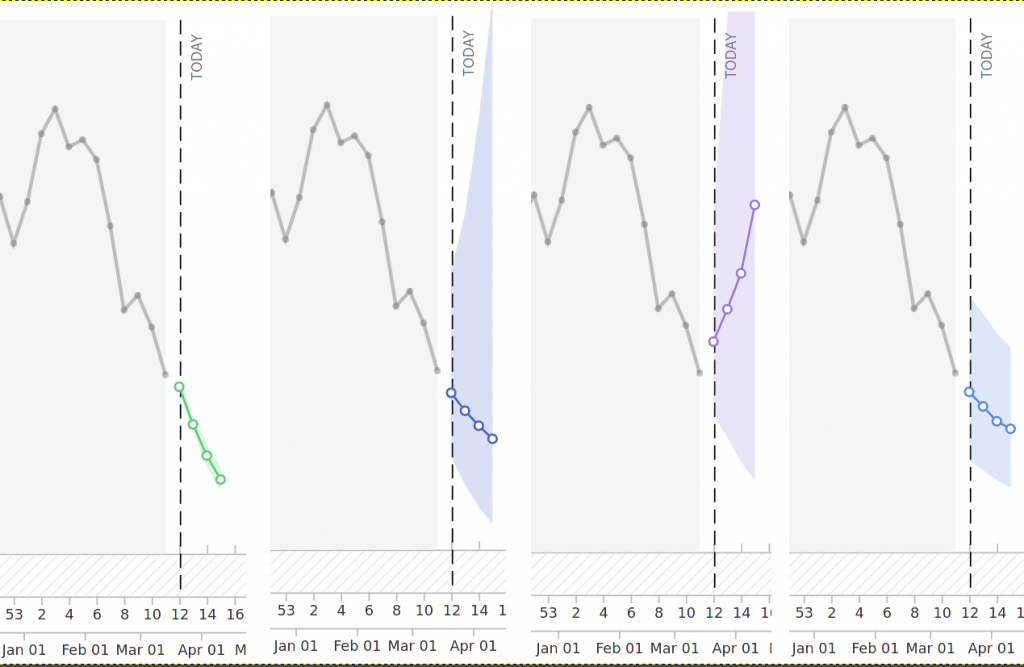

Forecasting is hard. And some of the predictions are bad. Some are really good, but some have obvious flaws. Being critical is always easy in hindsight. So to avoid giving me the benefit of hindsight, I’m showing you some examples from the latest death forecasts submitted to the US Forecast Hub:

The first forecast is much too certain, the second one is probably too uncertain to be useful and the third one is just YOLOing around. The fourth one looks almost decent, but its uncertainty shrinks with the forecast horizon. Uncertainty should increase over time, as we are naturally less certain about what happens in a week than in a month. This, of course, is an unfair selection. If you look at the website, you will find some really good forecasting models. Also, the ensemble of all models submitted to the US Forecast Hub usually performs very well.

Designing and coding a forecasting model is not easy and it takes a lot of tweaking and tuning to avoid all the pitfalls described above. The question I have asked myself for the last few months is: can humans do better? Are computer models able to systematically beat someone with a pencil who draws lines on a piece of paper?

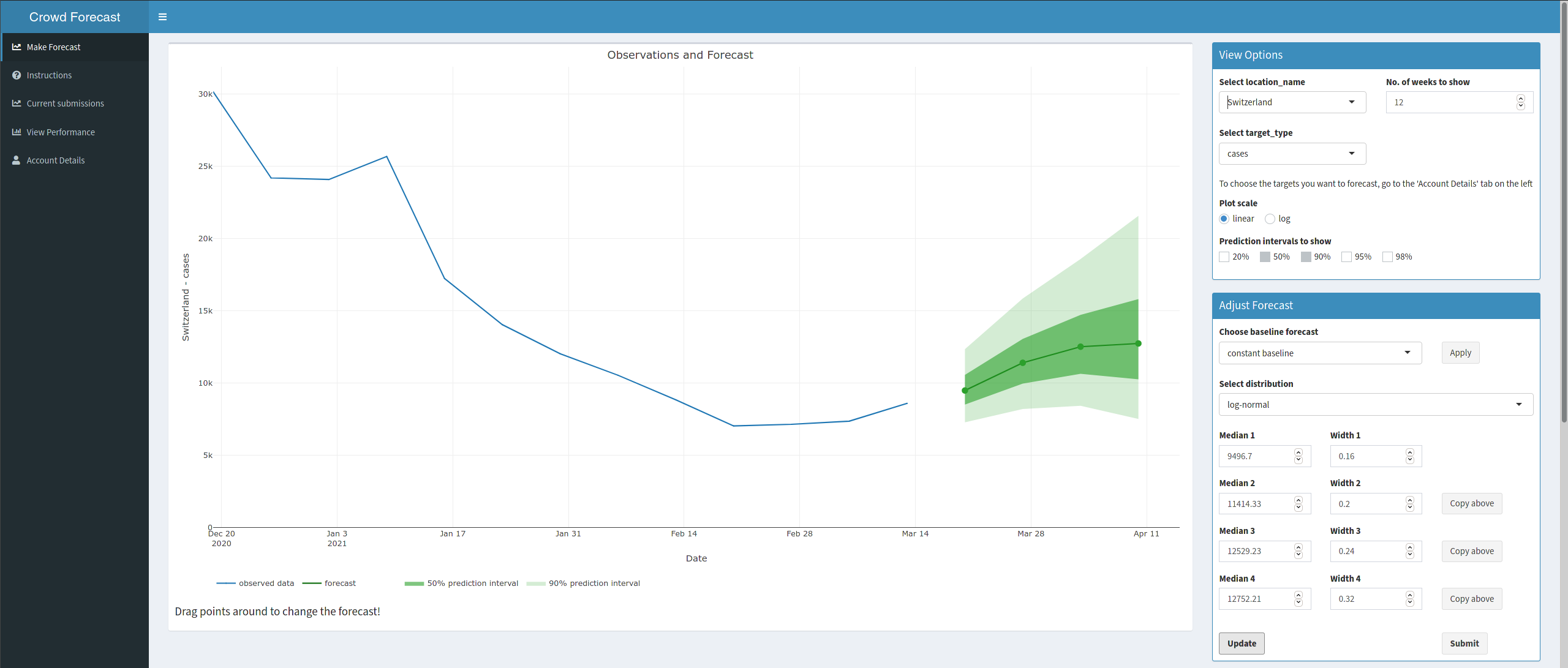

To answer that questions I set up an app called crowdforecastr (code here). The app allows users to make forecasts about Covid-19 case and death numbers. The catch with this app is that the forecasts are directly comparable to predictions made by computer algorithms. Other platforms like Metaculus or GoodJudgement also ask users for predictions, but these follow a completely different forecasts than most other epidemiological predictions, which makes it somewhat hard to compare them.

Over the past few months we have submitted forecasts for Germany and Poland to the German and Polish Forecast Hub (here is a summary about this I wrote earlier). Between October and December 2020 our crowd forecasts consistently outperformed most other models. This doesn’t mean that we haven’t been horribly wrong at times. But it does mean that humans don’t need to shy away from the comparison against computer algorithms. Recently, even German politician Karl Lauterbach tweeted a screenshot of our forecasts.

On March 8th 2021, our working group launched the European Forecast Hub in collaboration with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). We therefore expanded our crowd forecasts quite a bit. Users can now submit predictions for 32 different European countries. These predictions get collected and aggregated every week and submitted to the European Forecast Hub. We are always looking for new forecasters!

Here is an overview of the facts:

- you can find all relevant information on www.crowdforecastr.org, including an introduction on how to get started (and a video!) and what you should think about to make a good forecast

- you can create a new account and start forecasting on app.crowdforecastr.org

- New data comes in every Sunday at 9am CET

- Forecasts can be made until Monday 11pm CET